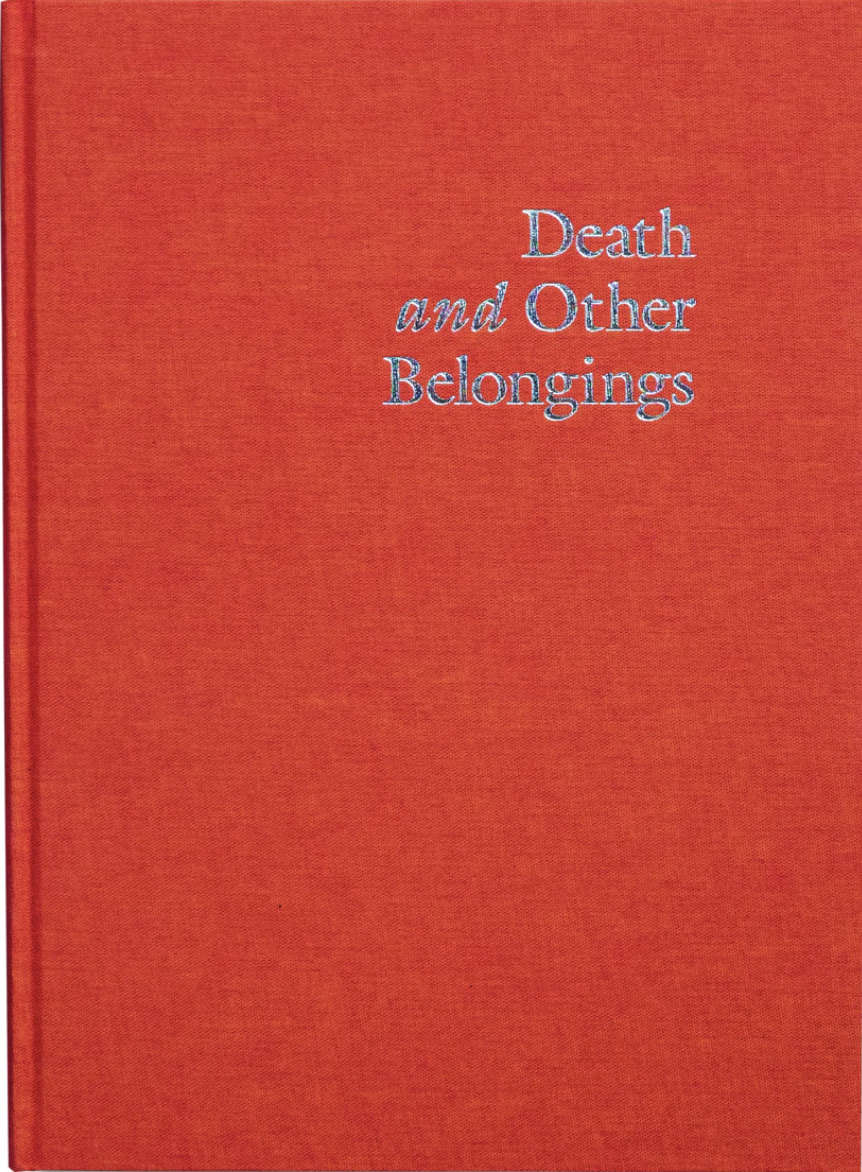

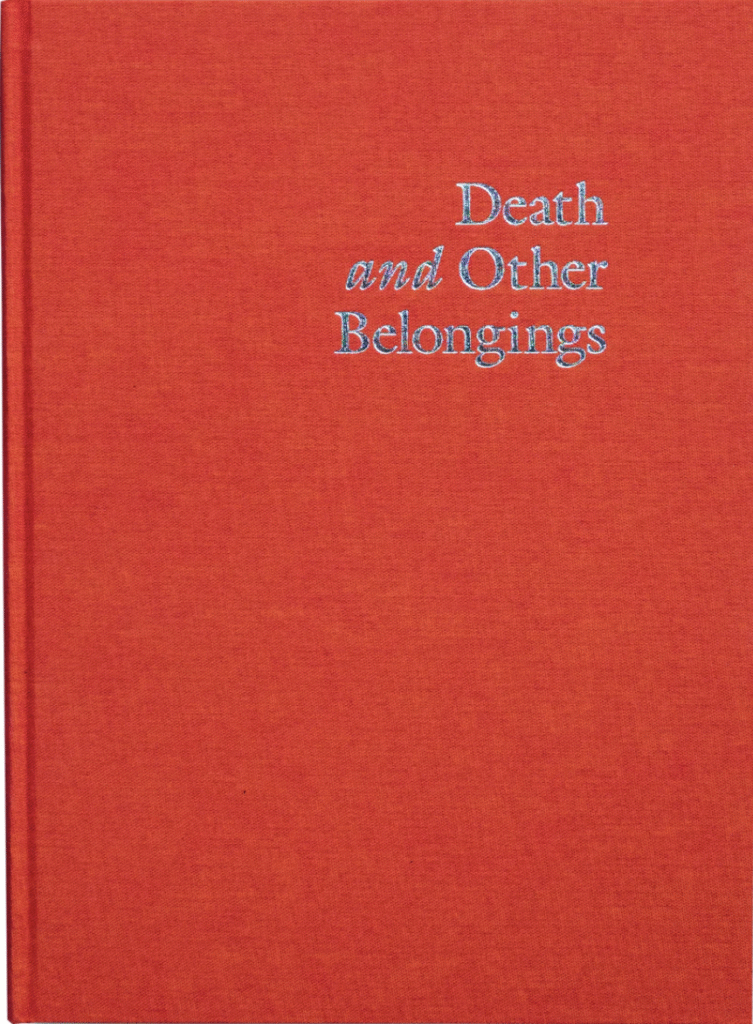

Book Review – Death and Other Belongings by Will Green

Book Review – Death and Other Belongings by Will Green

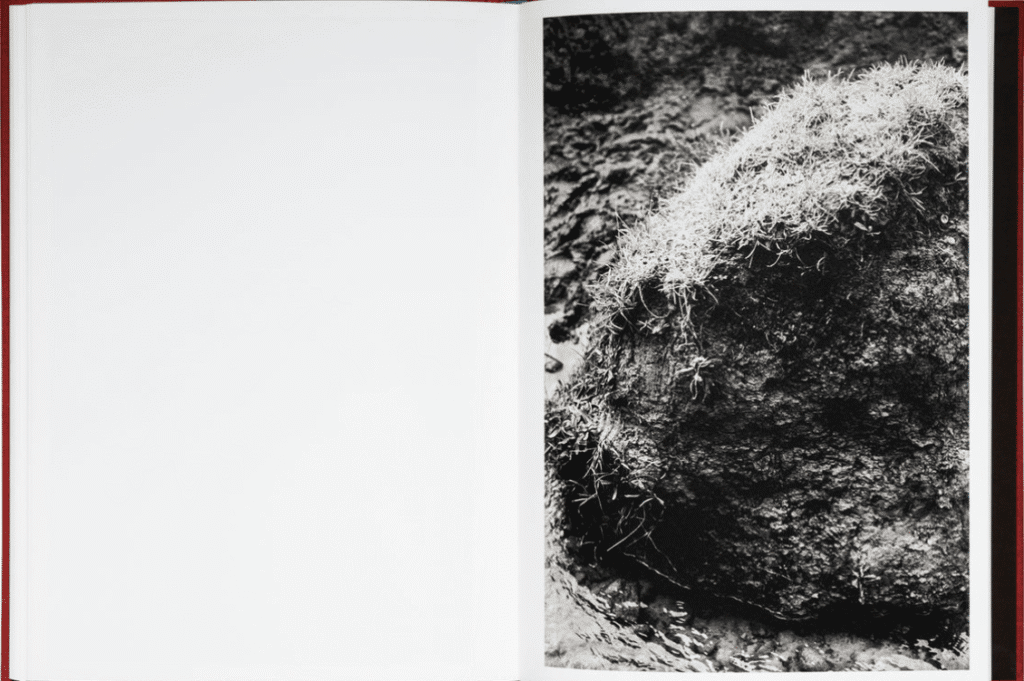

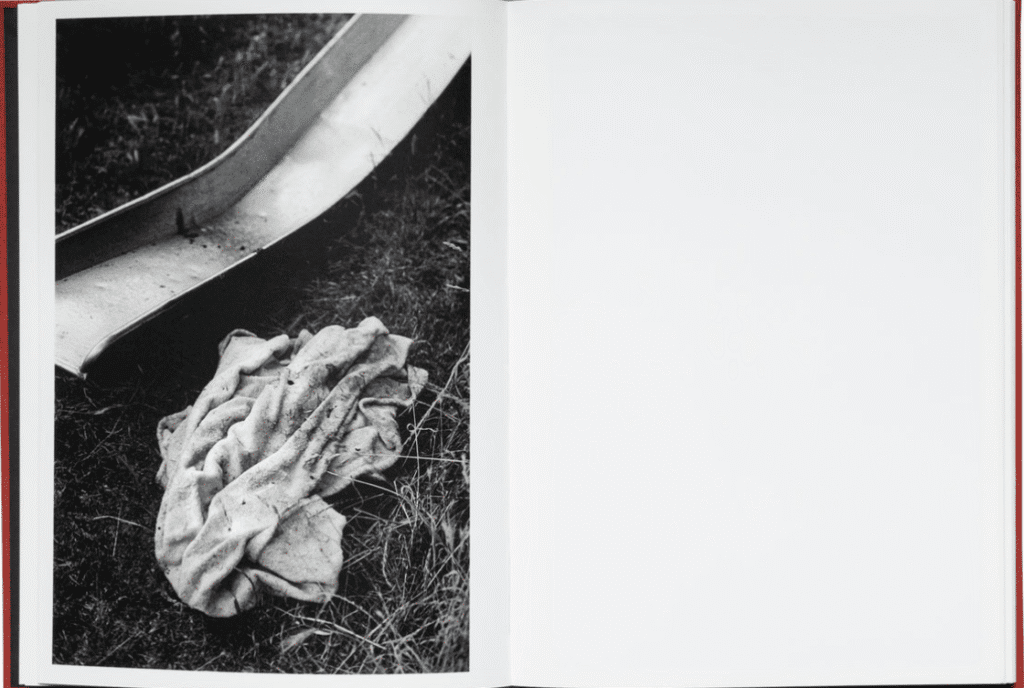

Will Green’s Death and Other Belongings refuses to instruct the viewer on what grief looks like. Instead, it pulls the viewer into its atmosphere. The black-and-white photographs stay expansive yet restrained, devoid of the drama that typically accompanies grief. Green turns his camera toward what stays behind. He focuses on a chair in the garden, the fabric still creased by the weight of a body; a bee lies in the dust; apples sink into the soil. Each photograph insists that the world continues to act in its ordinary way. Green meets that continuation with steadiness and records it without ceremony.

Before the reader opens the book, the circumstances behind it already shape expectations. Green created these photographs after the deaths of both parents during the year he also suffered from Covid-19. GOST Books published the sequence in 2024 as his first monograph. The work grew out of the quiet months when shock had eased but daily debris remained. The project might promise sorrow or catharsis, yet Green directs his attention elsewhere. His photographs resist closure, concentrating on endurance.

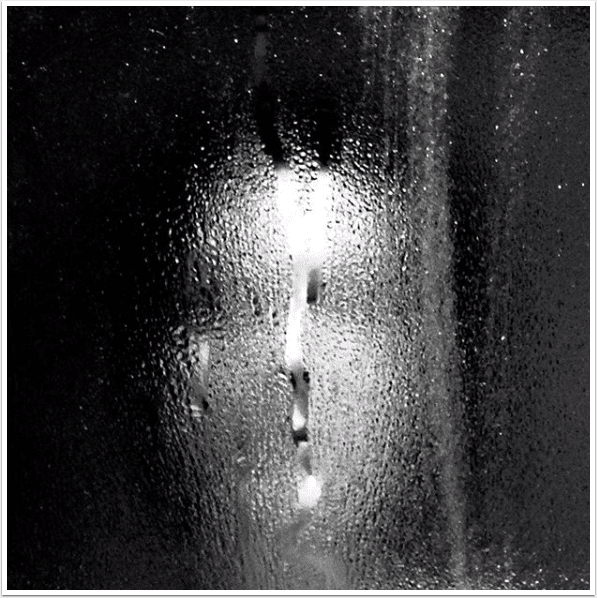

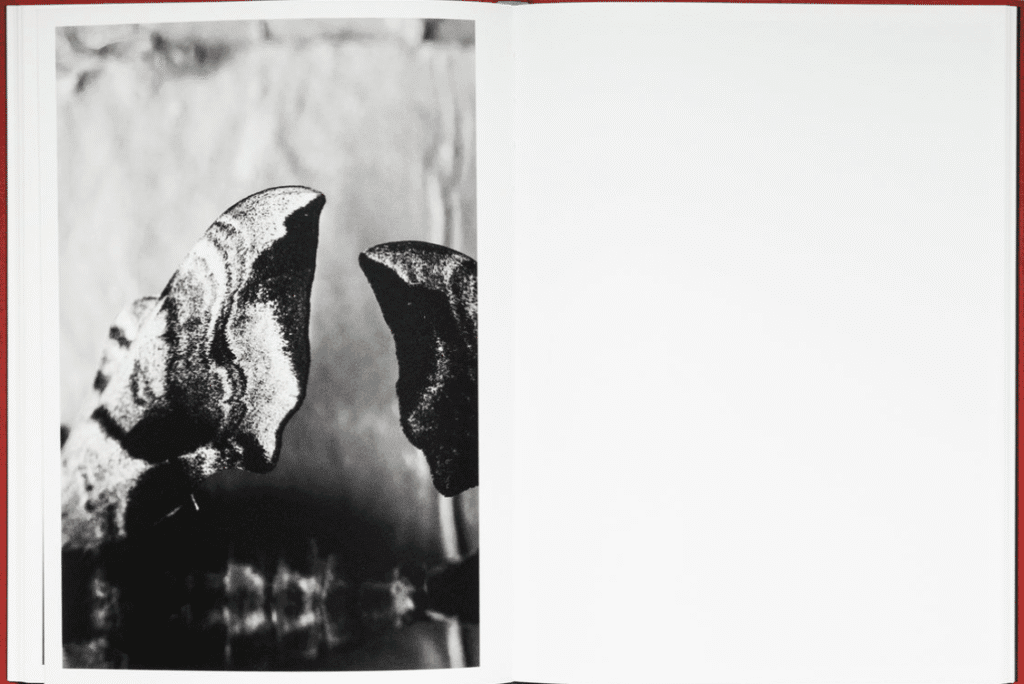

The photographs remain monochrome yet never cold. Grey tones breathe, and white surfaces carry the grain of memory. The scale stays domestic, while the gaze feels devotional. Each image carries what Roland Barthes named the punctum—that small detail that pierces the spectator, though Green lowers the volume of the sensation. The wound seeps rather than strikes and lingers once it arrives.

Green’s practice demonstrates how photography unsettles the concept of time. Each image traps the viewer in a loop where the past presses against the present, and the spectator, if willing to remain inside that pressure, hangs between “then” and “now.” The book depends on that suspension. Every photograph performs a small act of holding on.

A fire blazes in a dustbin; pillowcases drift on a clothesline. Moisture beads on glass. Bouquets lay upon caskets. Each scene suggests a held breath. The viewer feels the heaviness of what is gone. Julia Kristeva’s description of the abject—the point where boundaries collapse and the self touches what it cannot absorb—echoes throughout the sequence. These photographs avoid grotesquerie but disturb through their persistence at the edges of decay. A dead bee unsettles the neat borders of life. A chair retains an imprint. Absence exerts a physical force.

Many readers may approach Death and Other Belongings as a pandemic narrative. In one sense, they are correct: the lockdown restrictions gave the work its shape. Green could not travel; his world shrank to the distance of a short walk and the rooms of his house. The book illustrates how grief itself operates as a form of lockdown. It limits movement and charges every object with unbearable significance. A cluster of cobwebs, a flight of naked worn stairs, a patch of sunlight—each carries weight. The bereaved live within a museum of the ordinary.

Barthes described the photograph as a certificate of presence, a record proving that what appears in the frame has been. Green transforms that proof into haunting. Everything in his book has been, and that knowledge makes the present feel strange and fragile. His photographs refuse consolation and confront the viewer with the continuation of life. Apples decay, grass grows, and time presses forward.

One image stops the reader: clipped hair strewn upon bare boards, rendered in mid-tone grey. The picture could signal an ending or nothing at all. The caption gives no guidance. The photograph rests quietly, a small collapse turned tender. That restraint defines Green’s accomplishment. He treats mourning not as a spectacle but as a practice of sustained attention.

The arrangement of images feels intuitive rather than chronological. The sequence drifts—from outdoors to interiors, from still life to garden, field, and sky—before circling back again. A human chest marked with ECG stickers, a blurred close-up of a bee: both pulse with life, yet remain suspended in stillness. The rhythm hints at renewal but withholds redemption. The world beyond only deepens the sense of solitude. Green does not depict recovery; he documents endurance.

Following the sequence of photographs, towards the end of the book, typewritten text interrupts thoughts with the first ProMED-mail alert, which announced a “pneumonia of unknown cause.” The stark page breaks the rhythm. Its dry, factual tone pulls the reader from the quiet rooms into the public noise of a crisis. Green folds his private grief into the shared history of the pandemic, showing how personal loss never exists alone. It connects, often unwillingly, to a collective memory that surrounds it.

When readers ask what the book describes, verbs answer more accurately than nouns: lingering, noticing, remaining. The photographs behave like half-formed and continuous thoughts.

Green’s images show that the act of seeing carries its own memory. The photographs collect the debris of a moment and turn it into a surface for reflection. The camera acts not only as a recorder but also as a witness and a partner in endurance. In this book, the collaboration stays silent. His parents remain unseen. What survives are the things their hands once touched. He presents grief without sentimentality. Empathy comes through the world itself—the worn cloth, the sagging flower stem, the half-cleaned surface. The world continues to exist, and Green continues to attend to it.

The book asks for slow viewing. Its rhythm approaches a ritual. Turning each page becomes an act of patience. The repetition of looking turns into a form of prayer. Susan Sontag wrote that photographs haunt more than they explain, and Green’s do precisely that. They settle behind the eyes and stay there.

The work strikes a balance between restraint and emotion with care. It never reaches for drama, yet the viewer leaves hollowed. That emptiness does not equal despair; it signals recognition. The images refuse to instruct the viewer how to feel; they reintroduce the mechanism of feeling itself.

When photography works honestly, it gives the world back slightly altered, like hearing one’s own voice recorded. Green’s voice within these pictures stays quiet but steady. He refuses to dramatise the deaths of his parents; he registers their absence through shifts of light. That restraint holds ethical weight.

Artists such as Jo Spence and Hannah Wilke once photographed their own dying bodies as a declaration of control. Their work shouted. Green whispers. The moral force remains similar: a refusal to look away. His method avoids spectacle and allows decay to speak in its own language—cracked fruit, shadow, dust. The sequence argues for tenderness as a poetic stance.

Grief never follows a straight line. It circles, contradicts itself, and settles in unexpected corners. Green’s book moves to that rhythm. It does not begin or end in any conventional sense. Readers will return to the opening page to test whether the loss still feels real. The photographs expect this impulse; they welcome repetition. Each viewing alters them slightly, as though they age alongside the person looking.

Green likely worked alone, surrounded by absence, perhaps developing film in a kitchen sink, searching for meaning in light leaks and negatives. That process becomes a small resurrection. Holding an image under chemical water and waiting for the past to appear merges craft with faith. The act becomes both technical and devotional.

The title Death and Other Belongings sounds casual at first, as if death were one more object placed in a drawer. Yet the phrase reveals a deeper accuracy. Grief arrives quietly and settles inside ordinary life until it becomes part of gesture and breath. Green’s photographs gather those remnants. What remains after someone departs is not the furniture or the clothes but the light that still falls where they once stood, the faint shapes that persist in the air.

By the final page, the viewer breathes differently. The act of looking has slowed perception. That shift of rhythm marks the success of the work.

Green asks for patience. He invites the viewer to look without deciding what the image means, to see the ordinary as proof that connection changes shape but never disappears. In his hands, the camera listens rather than explains. The photos do not shout. They hum quietly at the edge of hearing, alive but restrained, like a memory that refuses to leave.

Many artists have confronted loss—some directly, some through performance—but few sustain such quiet intimacy. Green’s photographs converse rather than document. They ask what belonging means when what held us together has gone.

The pictures do not end when the book closes. They stay in the mind, faint but insistent, the way light leaves its shape behind your eyelids. Green understands that constantly looking changes the person who looks. The act pulls the viewer closer until attention turns into a kind of care. To see his work is to feel one’s own losses stirring somewhere in the background. He does not try to resolve that. He leaves the photographs to sit quietly in their own time, and the viewer will keep coming back, unable to step away.

To purchase this book, please click here

Please support us

TheAppWhisperer has always had a dual mission: to promote the most talented artists of the day and to support ambitious, interested viewers worldwide. As the years pass, TheAppWhisperer has gained readers and viewers and has found new venues for that exchange.

All this work thrives with the support of our community. Your support helps protect our independence, and we can keep delivering open, global promotion of artists. Every contribution, however big or small, is valuable for our future.