Peter Hujar’s Portraits in Life and Death: A Meditation on Beauty, Mortality, and the Intimacy of Looking

Peter Hujar’s Portraits in Life and Death: A Meditation on Beauty, Mortality, and the Intimacy of Looking

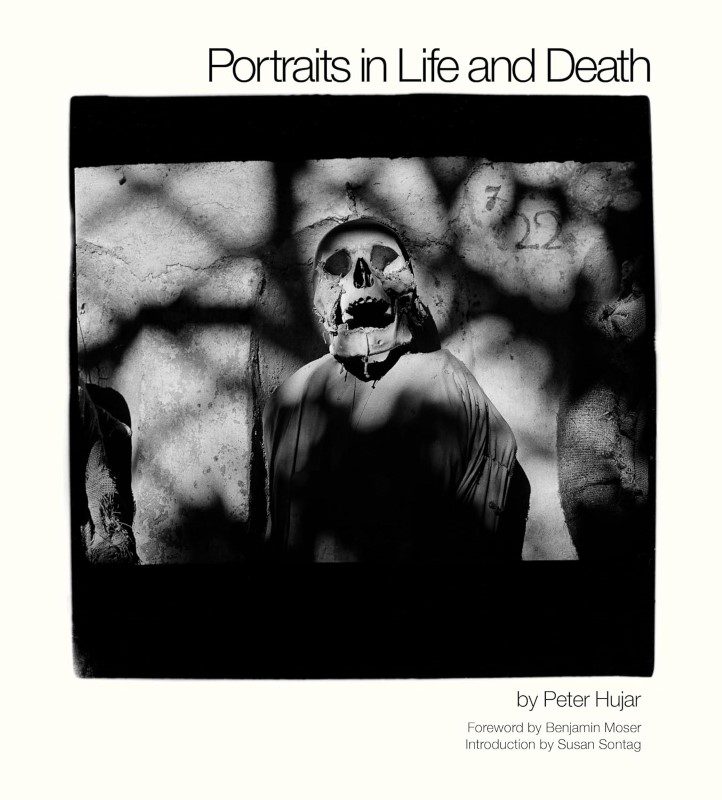

It’s almost impossible to open Peter Hujar’s Portraits in Life and Death and not feel that peculiar hush that settles over you in the presence of something both beautiful and unsettling. The book — first published in 1976 and reissued in 2024 — remains one of the most haunting and quietly magnificent works of photography in the twentieth century. It is not a grand statement, nor a coffee-table monolith of glossy spectacle. It is, instead, an austere, personal object: forty-one black-and-white photographs that carry within them an entire philosophy of seeing.

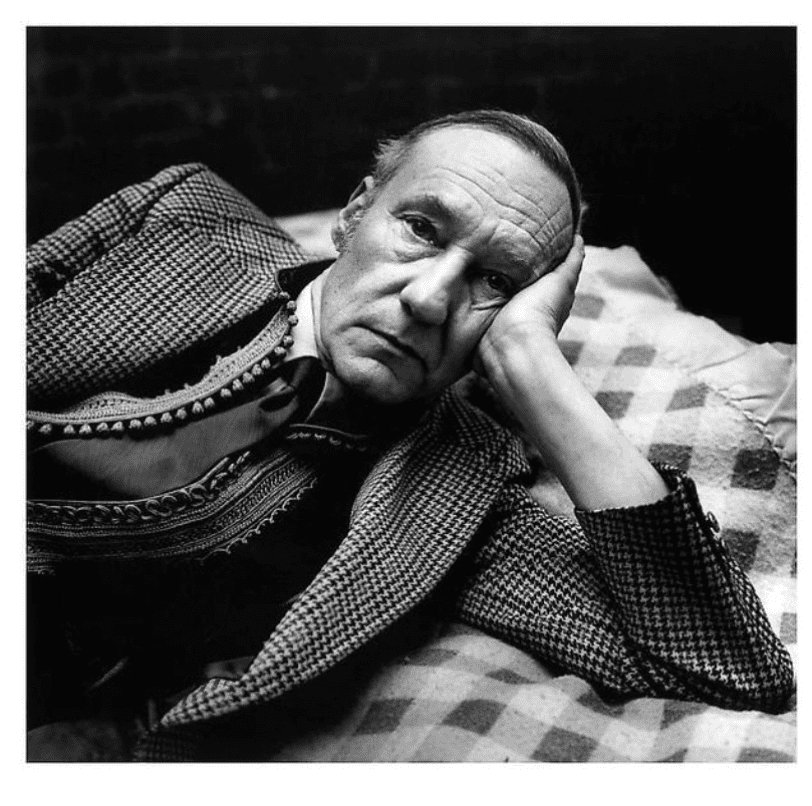

At first, the book appears deceptively straightforward. It begins with portraits of the living — Hujar’s friends, lovers, and contemporaries in New York’s downtown art scene of the 1970s. The images are simple, stripped of artifice. A face against a wall. A body reclining on a bed. A moment caught somewhere between awareness and dream. But then, at the end, something changes. The final section takes us into the Capuchin catacombs of Palermo, Sicily, where Hujar photographed mummified corpses hanging in alcoves and lined along the walls. These images of the dead — desiccated, fragile, dressed in their Sunday best — come only after we’ve looked into the eyes of the living. The effect is devastating. Hujar doesn’t hit us with death at the outset; he lets us arrive there slowly, almost tenderly, as though reminding us that the two states — life and death — are not opposites, but part of one continuous breath.

A Photographer Among Friends

Peter Hujar was, by all accounts, a man of contradictions. Sensitive yet difficult, reclusive but deeply empathetic, he resisted fame even as he sought to capture beauty. Born in Trenton, New Jersey, in 1934, Hujar came of age as photography was shifting from documentary form to something more personal and introspective. His work belongs to the lineage of Diane Arbus and Robert Mapplethorpe, yet it stands apart from both. Where Arbus was fascinated by the grotesque and Mapplethorpe by the stylised and sculptural, Hujar occupied a quieter space — intimate, melancholic, deeply human.

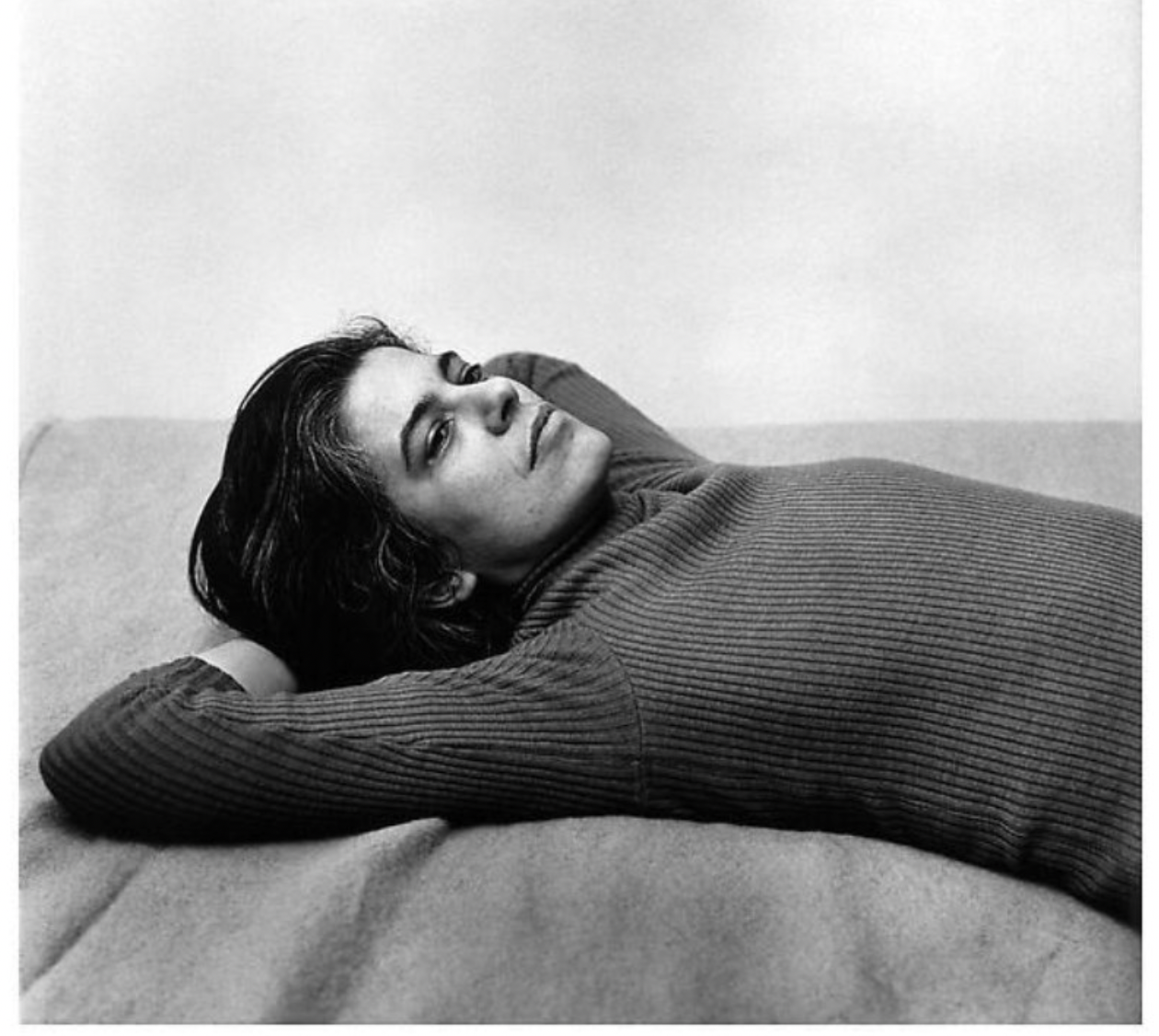

The portraits in Portraits in Life and Death were mostly taken between the late 1960s and early 1970s. His sitters were people he knew well — artists, writers, musicians, drag performers, and lovers who inhabited the same scrappy downtown world as he did. Among them were Susan Sontag, Paul Thek, John Waters, and Divine. There is an extraordinary gentleness in the way he sees them. You never get the sense that he is performing photography; rather, he is sharing time with them, allowing the image to surface naturally. Hujar’s gift was his patience. He waited for stillness — for that moment when the sitter dropped the performance of self and something unguarded emerged.

Take, for instance, his portrait of Sontag. She’s lying back, self-contained, the gaze turned away from us rather than into the lens; no theatrical lighting, no clever staging — just a person caught between thought and silence.

In her introduction to Portraits in Life and Death, Sontag writes: “Photography … converts the whole world into a cemetery. Photographers, connoisseurs of beauty, are also—wittingly or unwittingly—the recording-angels of death … [In] this selection of Peter Hujar’s work, fleshed and moist-eyed friends and acquaintances stand, sit, slouch, mostly lie—and are made to appear to meditate on their own mortality. Do meditate, whether they … acknowledge it or not. We no longer study the art of dying, … but all eyes, at rest, contain that knowledge. The body knows. And the camera shows, inexorably. The Palermo photographs—which precede these portraits in time—complete them, comment upon them. Peter Hujar knows that portraits in life are always, also, portraits in death.”

The portraits of his friends and lovers share this same atmosphere of quiet intimacy. Some are clothed, others nude, yet none feel voyeuristic. The body, in Hujar’s world, is not spectacle; it’s simply a vessel for light and feeling. His photographs invite us to linger — not in the way one gawks, but in the way one listens.

Susan Sontag’s Mirror

Sontag’s introduction to the original edition is short, sharp, and prophetic. She wrote, “Photography is the inventory of mortality. Photographs state the innocence, the vulnerability of lives heading toward their own destruction.” It’s one of those lines that changes how you see the entire book. It also defines the strange duality at its core: every photograph is both an assertion of presence and an announcement of absence. Hujar understood this instinctively. To photograph someone, after all, is to admit they will one day be gone — that the photograph will outlive them.

Sontag and Hujar were kindred spirits in that regard. She once described photography as a “melancholy act of preservation”, and his pictures are exactly that: melancholy without being morbid. The portraits celebrate aliveness while acknowledging, quietly, that it cannot last.

The Palermo Photographs: Death Without Drama

Then come the Palermo images. After so many living faces, the sight of the mummified dead takes you aback. Hujar photographed these figures in the Capuchin catacombs during a visit to Sicily in the late 1960s. The catacombs themselves are one of those places where the boundary between reverence and horror blurs: thousands of preserved bodies, dressed and arranged by social status — priests, soldiers, children — all suspended in time. Many photographers have documented the site, but none with Hujar’s restraint. There is no sensationalism in his approach, no attempt to shock. The dead are given the same calm dignity as his living sitters.

In one image, a man’s face is reduced to parchment skin and hollow eyes, yet Hujar’s composition softens the grotesque. The figure is illuminated gently, the shadows respectful. These aren’t “memento mori” in the heavy-handed sense; they are extensions of the portraits that precede them. It’s as if Hujar is saying: this is what comes next, this is what we all become — and isn’t it, in its way, still beautiful?

The decision to end the book with these photographs rather than begin with them is crucial. By first leading us through life — through the faces of those he loved and lived among — Hujar prepares us to meet death with empathy rather than fear. The sequence invites reflection: each living face becomes a prelude to the dead ones, and each dead face echoes back into the living.