The Democratization of the Photographic Image or How I learned to Stop Worrying & Love the Camera Phone

For the past week I have been working on an essay examining whether mobile phones have affected our choices of subject matter and how we take photographs. During the course of my extensive research for this project I came upon an excellent article written by Erin Jennings, a fine art photographer and faculty member in the University of Memphis Department of Art. Her article entitled ‘The Democratization of the Photographic Image or How I learned to Stop Worrying & Love the Camera Phone’, I have republished it here with kind her permission. (foreword, Joanne Carter).

Contributed by Erin Jennings.

Erin Jennings is a fine art photographer and faculty member in the University of Memphis Department of Art. erinjenningsphotography.com

Originally published in Number Magazine: Issue 92, Fall 2017. Reprinted with permission of the author.

Due to the proliferation of digital photography in the 21st century, over 1.8 billion images were uploaded to the Internet daily in 2014 via various social media platforms . Instagram alone is responsible for a total of thirty billion uploaded images since it’s inception, with an anticipated 111.6 million users by 2019. The accessibility and instantaneous nature of the photographic image afforded by the camera phone era has induced a paradigm shift that has fostered a transformation in the way we consider photographic imagery. While professional photographers and members of the academy have scrambled to maintain their place in the photographic hierarchy, photography and photographic language have become apparatus of the people, creating a complex and perpetually evolving mosaic that exhaustively reflects contemporary culture. This broad discourse regarding the digital evolution of photography is multifarious and it narrows the dialogue to acknowledge the following points when considering the proliferation of digital imagery and it’s impact upon art making, the viewer, and the mass public.

Since it’s inception, photography has struggled to establish itself as an art rather than representational images afforded via an instrument of technological advancement and significant movements in photography have largely been reactions to the assertion that photography is an inferior art form due to the delivery of the image via mechanism. With the rise of the digital era in the 2000’s, photography again found itself amid an internal struggle regarding the digital process and the democratization of the visual image. While professional grade DLSR cameras were still economically out of reach for most, the emergence of the camera phone gave photography to the masses in an unprecedented manner that dwarfed prior user-friendly methods of production. This move towards accessibility and subsequent backlash is certainly not new. Photography pried portraiture from the wealthy, the Kodak Brownie brought the camera into the home (“You press the button, We’ll do the rest”), and the advent of the Polaroid gave consumers a nearly instant image (and print) with little to no skill required. Not only has accessible digital photography threatened the commercial photography industry, it also threw into question the very self-worth of many photographers whose identities were mired in the exclusivity of the analog process. Amidst this great wailing and gnashing of teeth regarding the transformation of the medium, there has been a renewed interest in the alternative historical process. While wet plate prints, cyanotypes, tintypes, etc. never truly disappeared from the vernacular, alt process work now seems to be re-emerging in fine art explicitly as a response to the digital process, countering digital speed, ease and excess with deliberation, tactility and a renewed exclusivity nearly eradicated by the digital manifestation of the medium. Though it may be the case that new interest in alternative processes has undoubtedly produced authentic, arrestingly beautiful work that stands on it’s own merit, do consider that the panic over the transition to accessible digital photography should not intimidate nor dishearten those who can transcend the artifice of process. On new technological shifts in photography, Jeff Wall comments,

“I cling to the notion of photography as a medium insofar as it is an authentic way to achieve what we can call “the picture”. The physical nature of any medium has never been free from the conventional – and therefore historical – manners in which the physical elements have been handled. So, I don’t feel there is anything particularly new happening in photography in that regard”.

As digital/ mobile photography has become an essential linchpin in the photographic discourse, Susan Sontag’s assertion that photography maintains a western middle-class perspective that insists upon a sustained look downward is still substantiated by a systemic narrative framed by media outlets that dominate the photographic discourse. Though the yoke of media framing has not yet loosed documentary photography, the nature of the photographic rhetoric has certainly begun to sidestep the formerly narrow vernacular. Addressing the documentary form, John Berger’s and Martha Rosler’s late 20th century approximations of viewer impotency invoked by documentary photography should be reevaluated in the context of the era of digital proliferation. Berger arrives at the conclusion that documentary “photographs of agony” will illicit viewers to adopt a humanitarian cause pertaining to the imagery, or simply refocus the viewer upon their own moral inadequacy due to a lack of legitimate recourse when confronted with the pain and suffering of others. Rolser furthers Berger’s theory, similarly alleging that viewers will adopt a cynical distance from any images of suffering. She then asserts that what then becomes very unlikely is “that those who view images of oppressive or exploitative social realties will mobilize politically in hopes of transforming them.” Mobile photography has reimagined the role of the documentary photograph in that the accessibility of the medium no longer necessarily dictates the photographer as “other”. While the interpretation of the photograph still largely remains with the socio-political positioning of the viewer, the role of the photographer has become more egalitarian in nature. In The Anxiety of Imagery, Yasmine El Rashidi determines that,

“The photographs that emerged from the eighteen days of the Egyptian revolution captured what Egyptians could not have imagined until January 25 [2011], the first of those days. In the images that came out of the utopian city within a city, Tahrir (or Liberation) was not only diversity and a sense of the individual, but also immediacy, intimacy, an infinite series of fleeting moments, encounters, emotions, gestures, of humanity. In that square, where the process of image-making was democratized though technology and every Egyptian had not only a voice, but a platform – a democratically moderated one – the real essence of the Egyptian people was given space. This revolution – influenced, propagated, experienced, shared, memorialized, through the tools of image-making and technology – offered the world, for the first time ever, anunedited photographic portrait of the most populous country in the Middle East”.

In Tahrir square, “the camera became a nonviolent weapon aimed directly at the state, denouncing it” and the significance of the response to this imagery lies demonstrably in the hands of camera phone wielding citizen journalists. The photograph is no longer looking downward because of the new egalitarian nature of the medium. Rosler and Berger’s assertions are perhaps still salient depending on the perspective of the viewer, but there has never in the history of photography been a moment where photography has been so duly representative of a mass public. This phenomenon now manifests itself during every instance of social movement mobilization and armed conflict involving civilians; every mass political action is now significantly framed by its participants. While media framing is still spectacularly present, it has become a veneer of suggestion rather than an absolute immutable reality. The emergence of the mobile image both negates and reinforces Berger and Rosler’s assertions of complacency. Considering the photographer is no longer necessarily occupying the role of the other, and due to the immediacy of the dissemination of the image, photography now no longer necessarily has to circumvent mobilization. While this should be considered a victory for commonality, a nefarious counter to this positive materializes when one considers that the sheer number of images, and what equates to assault via photographic imagery, can lead to an overwhelmed consumer who is immobilized into a position of inaction.

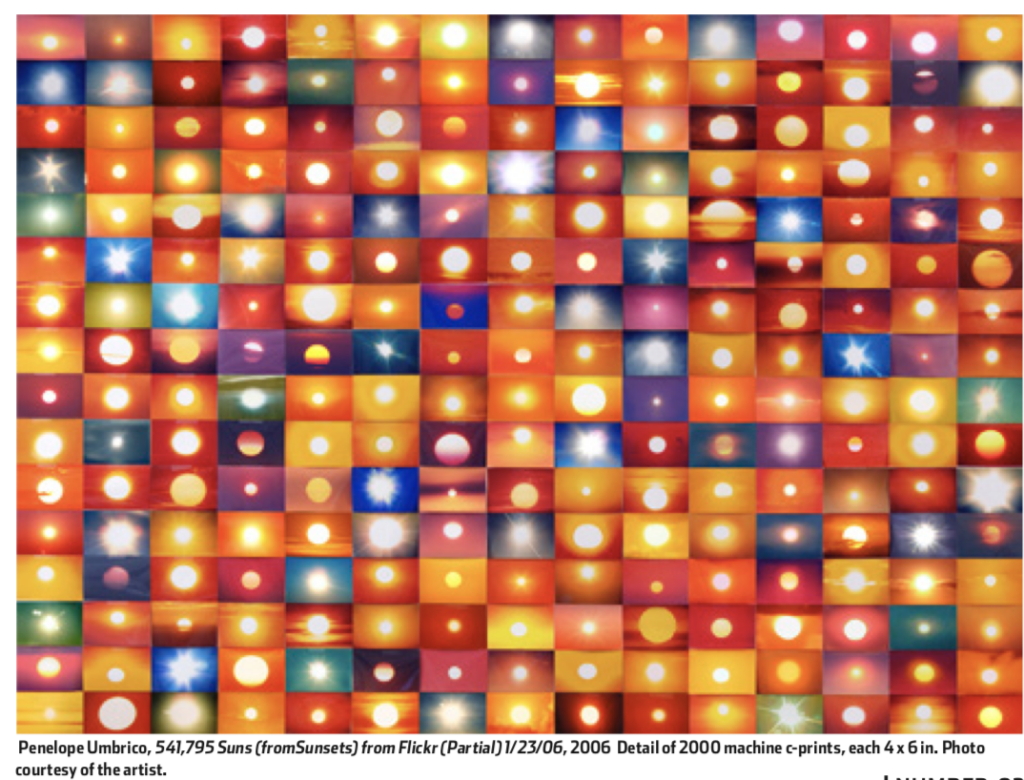

At this point, we now lay under siege from a ceaseless assault of imagery that perpetrates infinite redundancies. Dutch artist Erik Kessels exhibited 350,000 photographs from Flickr (the number shared in one day) in a gallery setting in order to “visualize the feeling of drowning in representations of other people’s experiences.” Similarly, Penelope Umbrico compiles nearly identical photographs uploaded to Flickr, exhibiting them in a rhythmic grid of repetitive imagery. While this barrage of imagery is in these cases aesthetically significant, it also illustrates the concept of imagery overload, which “is marked at times by general frustration, low-grade anxiety and flat-out fatigue”. Of larger concern, there is a common misconception that photographing an image with ones phone galvanizes memory and preserves the experience, but current research shows quite the opposite. Research conducted in 2014 by Fairfield University professor Linda Henkel determined that there is a photo taking impairment effect, which indicated that taking a photo in order to preserve memory actually diminished retention of the memory regarding the subject of the photograph. Henkel suggests that we have simply outsourced our memory to digital storage with little retention of the actual event. Consider this in conjunction with Sontag’s decades old assertion that, “viewers placed themselves behind the photographic camera in order to feel more empowerment and more willing to inhabit unfamiliar spaces. The viewfinder mediates situation by allowing the user to address a subject behind the known entity of the frame, protecting against the uncertainties of physical interaction”. The conjunctive conclusion is the existential implication that we are now viscerally experiencing our lives through screens with little retention of our reality. Our perception of our reality then is manifested via a compilation of manipulated/ curated images that ultimately are a manufactured fabrication of our own experience. Though perhaps without intention, we are certainly allowing the lens to consummately remove us from our life experiences and buffer not only the unfamiliar space, but also the familiar. Without caution, the very technology that enabled revolution may make cowards of us all.