Photo Book Review – The Afterimage of Looking: On Lee Miller, Witness, and the Persistence of Vision

Photo Book Review – The Afterimage of Looking: On Lee Miller, Witness, and the Persistence of Vision

When I first opened the book, Lee Miller, the temperature of the room seemed to shift — as if the light had turned to face her. Lee Miller was a name I thought I understood. Vogue model turned Surrealist collaborator, Man Ray’s lover in Paris, the war correspondent who walked through Europe’s ruins with a camera and a stare that could steady smoke. But this volume—edited by Hilary Floe and Saskia Flower, published by Tate Publishing in the UK and by Yale University Press in the United States—refuses the comfort of summary. It has been produced to accompany the Tate Britain retrospective now open, and it reads less like a catalogue than a re-encounter: a way of letting Miller’s images meet the present tense again.

The book’s curatorial intelligence matters. Hilary Floe, senior curator of modern and contemporary British art at Tate Britain, and Saskia Flower, assistant curator in the same department, have shaped an object that is at once rigorous and tender. Their editorship draws on new primary research and a broad archive of contact sheets, letters, and prints while resisting the impulse to smooth away contradiction. Their work sits within the broader vision of Alex Farquharson, Director of Tate Britain, whose stewardship of the museum’s programme has created the conditions for such a reappraisal—one that refuses to diminish Miller to anecdote or myth. In this, they are joined by Damarice Amao, associate curator of photography at the Musée national d’art moderne/Centre Pompidou in Paris, and Deborah Levy, novelist, playwright, and poet—author of the Booker Prize–shortlisted Swimming Home and Hot Milk—whose calibrated, luminous reflection sets an early pitch for the reader’s attention. The credits aren’t decorative; they acknowledge a chorus of eyes attending to a subject who has long been seen too narrowly.

What steadied me most as I read was a chapter titled, with a quiet shock of insistence, “She Is There,” by Levy. It opens like a slow exposure, allowing light to reveal Lee Miller’s interior landscape. Levy writes not to explain Miller but to dwell with her — to follow the trace of a woman who made herself visible on her own terms. The essay moves with a quiet precision, its rhythm shaped by the click of Miller’s shutter, its thought turning between the act of seeing and the desire to be unseen. Levy reimagines the studio as both sanctuary and stage: a place where Miller could escape the roles assigned to her — model, muse, subject — and become the architect of her own image. Throughout, Levy balances tenderness with clarity. She recognises in Miller a woman who transformed beauty into enquiry and vulnerability into art. The essay suggests that the photograph is not merely evidence, but a conversation — a dialogue between exposure and secrecy. In She Is There, Levy restores Miller’s complexity: not an icon, not a victim, but an artist at work within her contradictions. The title becomes a quiet insistence — that presence is its own resistance, and that to remain visible, on one’s own terms, is an act of creation.

My own research already informs my approach to attending to looking and pain. In my first-class honours degree dissertation, Reshaping Representations: Considering the Role of the Spectator in Contemporary Artistic Practices of Grief, Loss and Trauma, I examined how the Spectator (I capitalise the term after Barthes and Kuhn) isn’t a passive endpoint but a participant in meaning, addressed by images of grief and loss, altered by the encounter. I was concerned with how the photograph plays with time, how a single frame can hold the simultaneity of presence and absence. She Is There met those concerns where they live. The chapter didn’t explain Miller so much as stage the conditions of my looking: you are here, the image is here, and time has not finished with either.

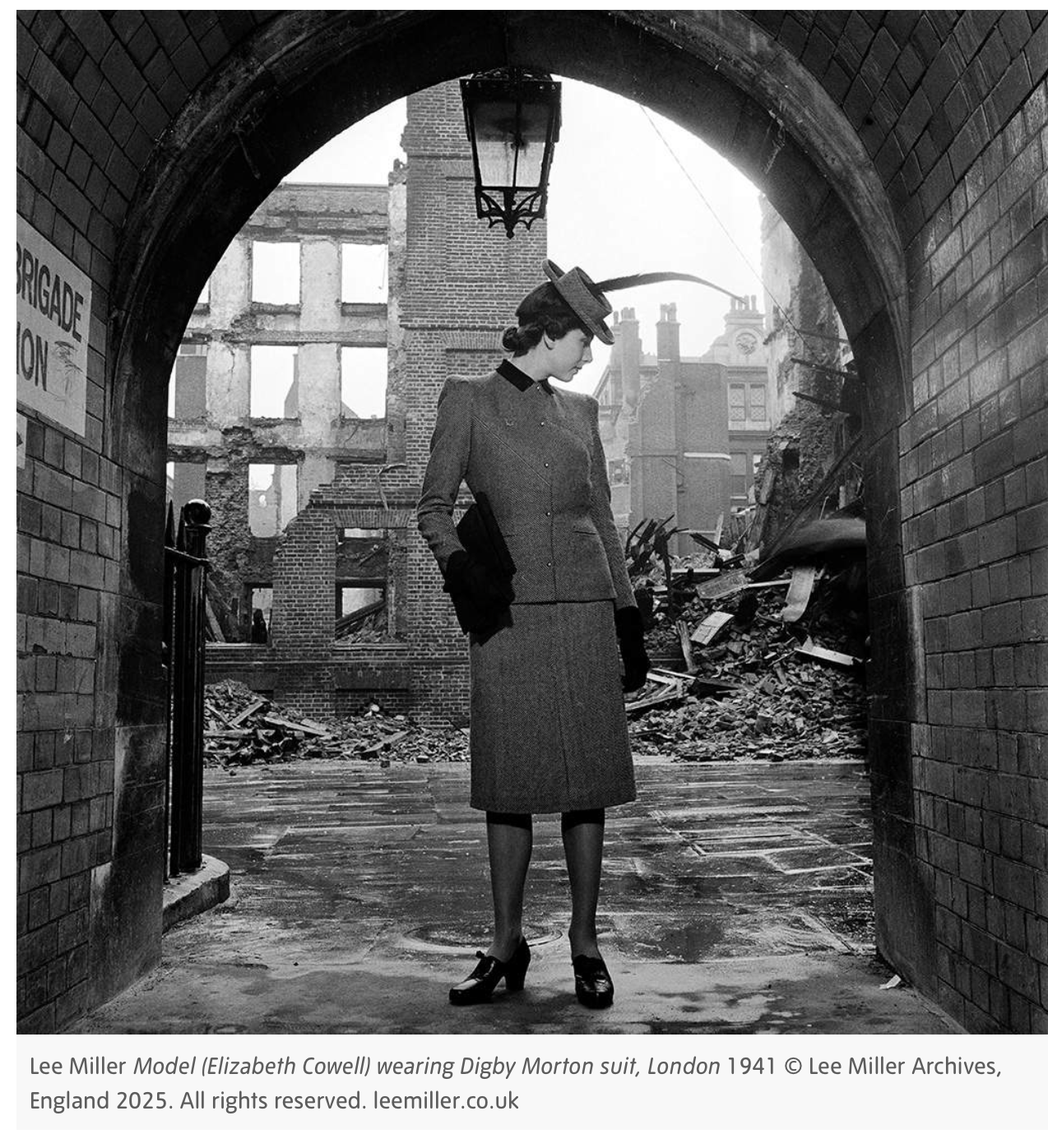

Miller’s biography lends itself to a string of nouns—muse, model, maker, correspondent, mother—but the book trusts images more than nouns. Early in the volume, the Man Ray years are allowed to breathe as collaboration rather than as a footnote. Miller learned in Paris how to use studio light like a verb. Together with Man Ray, she explored solarisation—the darkroom’s stroke of reversal where tones flip under a sudden exposure—an emblem of the Surrealist appetite for making the day dream of itself. The editors and essays are careful: solarisation belongs to Miller’s pre-war experimentation, not to her wartime practice, and its significance shifts from literal to formal and metaphorical as the years pass. It teaches a seeing that later survives without the technique. What changes with the war is the stake, not the intelligence.

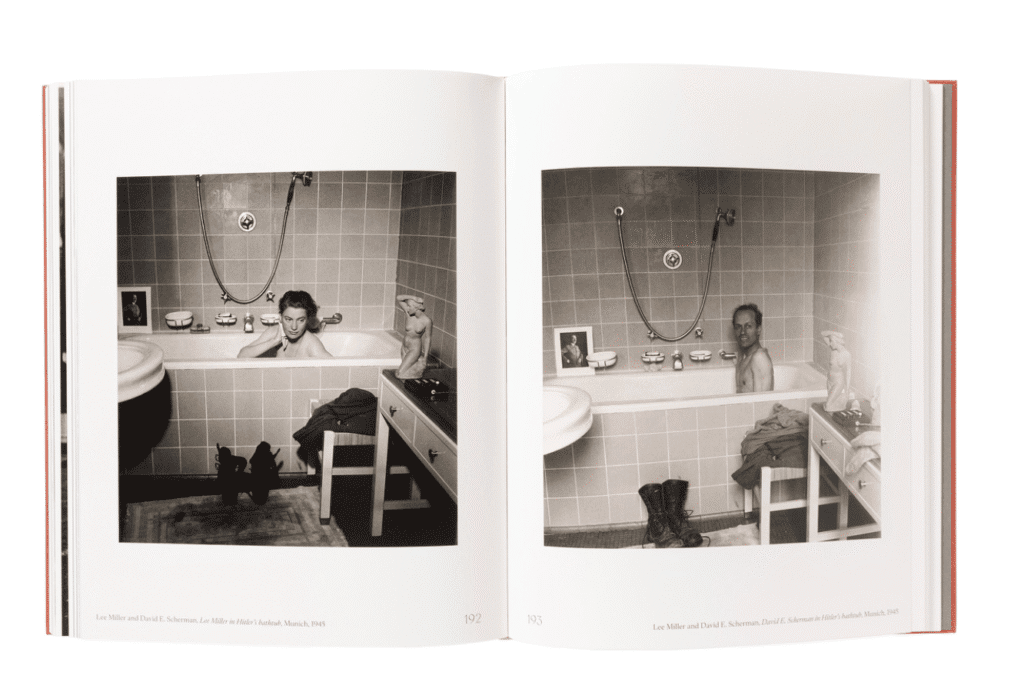

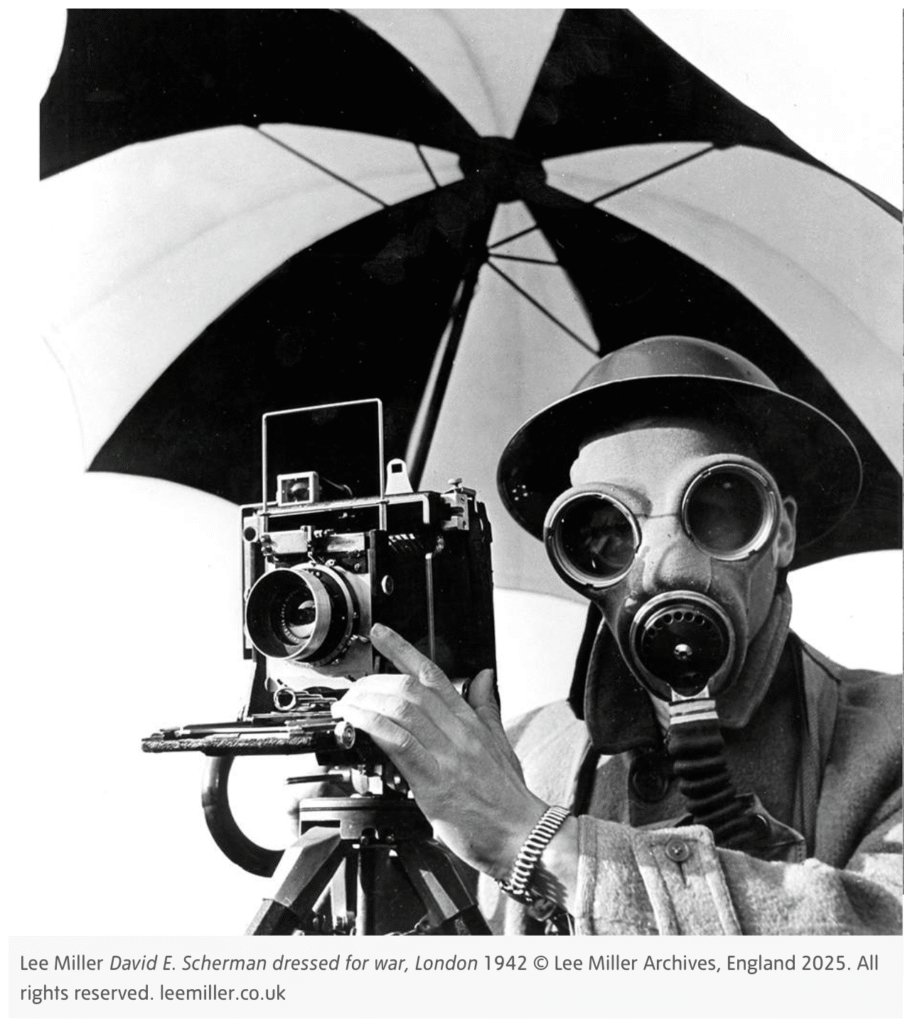

The chapter She Is There pulls into its orbit the image that has threatened to become legend: Miller bathing in Adolf Hitler’s Munich bathtub while her boots—still caked with the dirt of Dachau—rest on the bathmat. The photograph is more complex than the single frame suggests. On the edge of the tub sits a small, framed portrait of Hitler himself, deliberately placed there, a chilling reminder of the apartment’s owner and an object Miller refused to tidy away. The book restores context to the scene: adjacent frames, correspondence, accounts of the day’s unfolding. David E. Scherman, the LIFE photographer travelling with her, pressed the shutter. Earlier that day, Miller had been among those who entered the newly liberated Dachau; that night, they reached Hitler’s flat. The image does not read as triumph. It reads as the bitter theatre of a witness trying to wash a day off her skin.

It’s the folded uniform on the chair that catches me — absurdly neat, almost tender. That small act of order beside the chaos of the day unsettles me more than the famous boots on the bathmat. The ordinary sits next to the obscene, and suddenly the photograph feels alive again, not allegorical but painfully literal. Barthes’s “that-has-been” still applies, but here the past seems to leak; it hasn’t finished happening.

The image insists on the ongoing: not was, but is—presence that refuses to solidify into the safe amber of history. Julia Kristeva’s notion of the abject slides in beside the tub; the image unsettles thresholds between body and world, cleanliness and contamination, the intimate and the monstrous. And if Laura Mulvey’s gaze has any business here, it is to note the humiliation of fetish: the voyeur who came for a pin-up finds a woman who has witnessed atrocity taking a bath to survive the day. The image defeats consumption.

Deborah Levy’s essay—positioned around the beginning of the book’s writings (page 27) —tunes the eye to this frequency. Levy does not possess Miller; she keeps company with her. Her sentences are aerated and watchful, and they insist on the doubleness that looks like Miller’s signature: light that can be “luminous and scorched,” beauty that never forgets the dark it emerges from. Levy’s placement in the volume is not incidental; it launches a mode of looking—curious, tender, exacting—that the rest of the essays sustain. For a reader arriving via theory and personal stake, this is the key I was looking for.

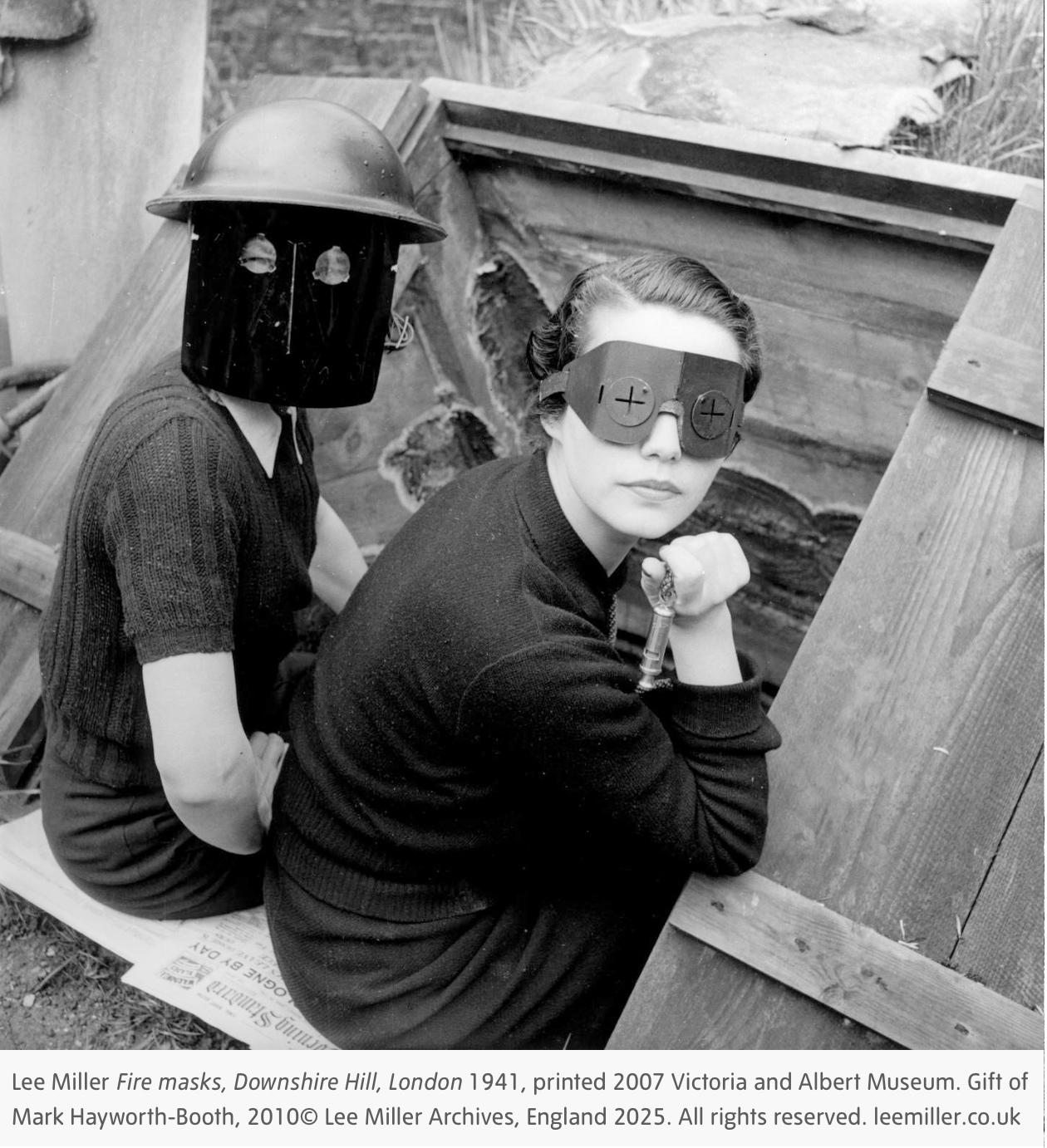

The wartime photographs are the most difficult to keep intact without explanation. Susan Sontag had it right: images of suffering can awaken or anaesthetise; they demand an ethics from the viewer that the image itself cannot guarantee. What strikes me about Miller’s war work (as sequenced in this book) is how it hesitates at the edge of moralising. The frames from Buchenwald and Dachau do not blackmail you into outrage; they present the facts before you and let your body register the aftershock. You can feel Miller’s exhaustion, her professionalism, her refusal to polish horror into digestible shapes. The London Blitz pictures, too, resist melodrama. A child’s toy among rubble is not posed to break you; it is seen with a geometry that keeps sentiment honest. The politics here is attention. To look precisely is to refuse forgetting. Where the book is especially persuasive is in refusing to cordon the war from the rest. Early fashion spreads converse with later ruins; a studio portrait meets a street scene scarred with ash. The proximity does not produce equivalence but a trace. The light that once articulated cheekbones will later insist on the factual texture of a wall, the sweat on a worker’s neck, the pallor of a face that has seen a camp.

The Surrealist experiments did not prepare Miller for catastrophe—nothing does—but they trained an eye that would not lie when catastrophe arrived. Damarice Amao’s contribution is invaluable here: she connects the avant-garde’s manipulations of light and inversion to a sensibility that later renounces manipulation without renouncing formal care. The through-line is not a technique carried into battle; it is an honesty about how light exposes what it touches. To speak of Man Ray is to step into a climate system. The book keeps him in weather, not as a biography’s pivot point. He is a collaborator and a lover, not a guarantor. The Romance of Paris serves neither of them. What matters, in this telling, is that Miller left and that the work continued.

In England, she met Roland Penrose, married him, and later they converted Farleys House in Sussex into a place where artists gathered to talk, eat, and watch the sky change. Their son, Antony Penrose, would later preserve and champion her legacy. The late pictures—jars, eggs, a glass in a window—are not retreats so much as another pitch of attention: how to live after history has entered your kitchen by the boots. The book allows domestic life to be political without judgment or blame. Because this is a publication in the orbit of an exhibition, it sits with another set of facts that belong in the light: the show is open at Tate Britain—2 October 2025 to 16 February 2026—and it will travel to the Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris (3 April to 26 July 2026) before crossing to the Art Institute of Chicago (29 August to 7 December 2026). The dates matter not only for logistics, but also because each city will read the work through its own weather and news. London sees Blitz pictures with a local ghost; Paris will see Surrealism under its own streetlights; Chicago will make the American return leg look like a homecoming that isn’t simple. The book lets that transnational life hum behind the page.

If my dissertation urged anything, it was that the Spectator is a relation, not a role. We do not stand outside images of grief and historical violence; we enter them at risk. Elizabeth Edwards’s “orality of imagery” helped me understand how photographs travel as stories—how we repeat an image to one another in phrases before we find it on a page. I first knew “the woman in Hitler’s tub” as legend, a sentence said at a party. Then I saw it: the uniform, the portrait, the curve of the tap, the boots on the mat. The book respects oral life by letting word and image braid together. In a culture where captions often overwrite photographs, it is rare to be given this much trust: look, then read, then look again. Deborah Levy’s contribution deserves a second paragraph because it organises the book’s tone. She brings literature’s economy to bear on a life often told too loudly. If biography tends to flatten an artist into a single genre, Levy insists on simultaneity: model and maker; glamour and report; tenderness and steel. Her prose keeps the work modern not by analogy to now but by listening to the pictures as if they speak a language we still share. That is the kind of contemporary I trust.

What, then, is the shape of the argument this book makes—if it makes one? Perhaps only this: Miller’s presence is an ethical style. The photographs do not require the viewer to solve them; they need the viewer to stay. To remain inside the discomfort of a room where the smallest objects (a towel, a toy, the way light finds a chipped saucer) have been drafted into witness. To attend without either fetishising or fleeing. In my dissertation’s terms, the Spectator is asked to accept the punctum without theatrics and to allow the abject’s threshold to teach a kind of care rather than a new disgust. The work’s politics reside in its stamina.

It would be easy to close on legacy and influence—on how Miller has been newly present in films, articles, and rooms—but I prefer the stanza the book keeps returning me to: the afterimage. In optics, persistence of vision is the ghost a bright thing leaves on the retina after it has gone.

In history, it is the way an image continues to structure what we see next. I finish the book and find that daylight has adjusted by a stop or two: the wash of morning across a window; steam lifting from a mug; the exactness with which a boot leaves a print on a bath mat.

Miller’s photographs have decided that these ordinary sights aren’t ordinary. They belong to the same world as Dachau and Paris and Farleys; they insist that the day carry the memory of what it has seen. Because this is an exhibition book, a companion to rooms I have not yet walked, I keep an itinerary close: Tate Britain, 2 October 2025–16 February 2026; Musée d’Art Moderne de Paris, 3 April–26 July 2026; Art Institute of Chicago, 29 August–7 December 2026. The show will encounter three publics and at least as many climates of attention. Each city will bring its own archive to meet Miller’s; each will test how A Life with Art, War and Surrealism sounds when the nouns are allowed to change key. I will carry the book with me when I go, not as a guide so much as an instrument—something to keep my looking in tune. It seems right to end where the editors and contributors began: with care. Hilary Floe and Saskia Flower have not assembled a pedestal but a field. Damarice Amao extends that field towards Paris with the precision of someone who knows how Surrealism’s experiments mutate in new weather. Deborah Levy opens the gate and asks us to enter, alert. The result honours Miller without monumentalising her, which means it keeps her moving.

The images never cease to act; they are not receipts for what once happened but actors in what happens now. So I return to the sentence at the heart of this review and the book it loves: she is there. In Paris and Munich, in London and Sussex, in a page and on a wall, in the bath and in the camp, in a glass of water making noon visible, in a toy lit like a wound. She is there, and because of that, we are here—Spectators not as voyeurs but as witnesses, learning, again, the slow craft of attention in a century that keeps trying to cancel it. If pictures still have moral life, it is because they persuade us to remain in a room long enough for presence to register.

Miller’s best work does precisely that. The light arrives; the shutter falls; the page turns; the image continues. The afterimage stays.

Please support us

TheAppWhisperer has always had a dual mission: to promote the most talented mobile artists of the day and to support ambitious, interested viewers worldwide. As the years pass, TheAppWhisperer has gained readers and viewers and has found new venues for that exchange.

All this work thrives with the support of our community. Your support helps us maintain our independence, allowing us to continue delivering open, global promotion of mobile artists. Every contribution, however big or small, is valuable for our future.